The Risk of Low Risk

Risk is unavoidable.

About a year ago, I wrote a short series on risk. In these three articles, I talked about the idea of risk, the difference between risk and volatility, and how we can reframe our goals in a way that makes risk more tolerable. If you would like a primer on risk (or just curious about my thoughts on risk), check out About Risk, The Wiggle, and Risk Realized & the Goal Window.

The allure of low risk

But for now, instead of ruminating on the characteristics of risk, I want to talk about a different concern.

Common wisdom says that we should avoid risk as we get closer to our financial goals. For instance, if you are saving for a child’s education in a 529 plan, we know the underlying investments in the account should get more conservative as your child approaches college age. A 30% drop in the stock market when your child is 4 years old isn’t a big deal. A 30% drop when they’re 18 can make your college goals much more difficult. More conservative investments can prevent those dramatic drops.

The same wisdom works for many other goals. Buying a car in 3 years, saving up for a new roof, and establishing an emergency fund are good examples. These are all goals that typically require more conservative investing. That is, the potential growth that comes with higher risk is not worth the chance of losing value in the short-term (when you need it). More on this later.

What is low risk?

Before we continue, it’s important to talk about what I mean by low-risk investments. Simply, this refers to types of investments that are focused on preserving capital and typically do not lose value. Investors tend to use treasury bonds to fill this need. Other vehicles for low-risk investing include money market funds and high-yield savings accounts. No matter the vehicle you choose to pursue low-risk investing, the idea is the same: You should expect low returns, but the returns will be consistent and you probably won’t lose anything (or very little if you do). You won’t lose money, but you won’t see high returns, either. You’re simply trying to preserve principal.

The cost we pay

When we talk about the balance of risk and return, we usually talk about risk as the inherent cost we pay for returns. That is, investments with higher expected returns will come with higher risks associated with them. An investment with an expected long-term return of 10% will have a higher degree of risk than an investment with an expected return of 6%. Yes, you will probably see higher returns over the long-term, but you may lose 20-25% in the meantime. Higher risk is the price we pay for higher returns. Even though it doesn’t cost us anything (until we sell), we still suffer through large swings up and down as we pursue greater return.

When we talk about lower-risk investments, the price we pay is different. Based on the example above, you may think there is little cost associated with low-risk investing. After all, since there is little to no risk, there is little to no inherent cost, right? There is a cost, but the idea is flipped. If higher risk is the cost we pay for higher returns, lower return is the cost we pay for lower risk. We may suffer higher degrees of risk in pursuit of higher returns, but we must accept low returns when we need less risk. It is the cost we pay.

Less finite goals

Earlier, I discussed a few goals that should use low-risk investments. It’s important to note that these goals have something in common; they are short-term and finite. That is, there is a defined point in the short-term when these funds will be needed. And yes, while an emergency fund might not be needed in the short-term, we need to treat it as such. We may need the money tomorrow!

What about goals with longer timeframes? What about goals with less finite needs? Perhaps the longest term savings goal most people pursue is the goal of retirement.

When we’re young, saving for retirement is not very finite. We may have an arbitrary age in mind, but the idea of retirement is too far in the future to know what it will ultimately look like. More aggressive investing is perfectly appropriate for those savers. Not only are they unsure about their retirement needs, they have a long road to let their investments grow (and recover from any downturns).

But what about retirement savers that are closer to their goal? By the time we’re 50-55 years old, the vision of retirement begins to take shape. We begin to have an idea of what age we might like to retire and begin enjoying the fruits of our labor and savings. Typically, this is the point when common wisdom advises us towards conservative investing. Near retirement, our long-term goals turn into short-term goals. Also, a finite point emerges when we will begin counting on our savings to support us. Now is not the time to be aggressive. Makes sense.

The cost, revisited

But remember, when we shift our retirement savings to more conservative investments, there is a cost associated with it. That cost is in the form of low returns.

Let’s explore an example. Bill has saved his entire life and is retiring in 1995. He has enough saved for retirement and doesn’t want to take his chances in a volatile stock market. Bill decides to take the conventional wisdom of near-retirement investing and use US treasury bonds to guarantee his future. Since 10-year treasury yields have been between 6%-12% since 1985, Bill decides to invest in 10 year bonds and withdraw 4.5% a year to support himself.

Fortunately for Bill, 10 year bonds will continue to yield high enough returns over the next ten years. However, as we see, his good fortune does not continue:

Yes, his good fortune runs out in 2008 when yields drop below 4% and do not recover for another 15 years, but it isn’t all bad news. If he began 1995 with $1,000,000 and withdrew $45,000 each year, he would arrive at 2025 with a balance of $749,187.56. Not too bad!

But, inflation

The problem with conservative investing is two-fold: 1) Low-returns and 2) the impact of inflation. You could argue that inflation is a factor with any investment, but its impact is relative to the amount of expected return.

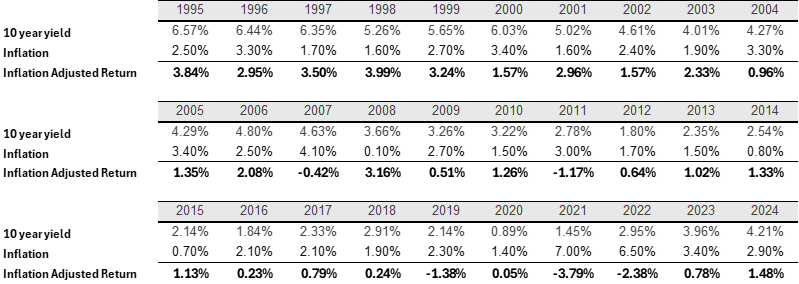

Here again are the 10-year rates along with inflation data from each year and the inflation adjusted return.

When we consider inflation, the results are dramatic. While yes, you can argue that the actual nominal returns are enough to support Bill’s withdrawals of $45,000 a year, but he would need to adjust his withdrawals annually to keep his standard of living steady. If he did not do this, his $45,000 withdrawal in 1995 dollars would be worth $20,770.97 in 2025.

Should Bill adjust his withdrawals each year to keep up with inflation, his otherwise sustainable retirement savings are in peril. That is because he must keep increasing his withdrawals every year to sustain his retirement goal. So if he withdraws $45,000 in 1995, he must withdraw $46,485 in 1996, $47,275 in 1997 and so on. The result: instead of over $749,000 remining in 2025, his savings would completely expire by 2023.

Keep the term in mind

The key to avoiding this problem is all about how we consider our timeline. Bill’s mistake was not in his desire to become more conservative. His mistake was not understanding his timeline. This is a common mistake, too. The problem occurs when we consider the beginning of retirement as the end of our financial goal. The goal of retirement is actually two parts: the accumulation phase and distribution phase. Seeing the end of the accumulation phase as the end of the plan leaves the distribution phase vulnerable to low returns paired with the corrosive effects of inflation.

The truth is, the financial goal of retirement extends long after we hang up our uniforms, suits, and hard hats. That is because retirement is not a finite point. Retirement is (hopefully) a 30+ year experience in which we need to support ourselves. It requires thought, careful planning, and some discipline.

Remember, conservative investments have their place: short-term and finite. In the long-term, these same investments aren’t as valuable. Yes, risk is unavoidable, but we aren’t required to accept needless risk. Being too conservative too early feeds the risk of losing to inflation; a risk we can certainly avoid.

Unsure about your allocation? Reach out today for a free consultation.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this blog is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or other professional advice. While we strive to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the content, we make no guarantees regarding its reliability or suitability for any particular purpose. Readers should consult with a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions. As a fiduciary Registered Investment Advisor (RIA), we are committed to acting in your best interests. However, past performance is not indicative of future results, and all investments carry risks, including the potential loss of principal.